The box office success of the film Oppenheimer, written and directed by Christopher Nolan, cannot be denied. Three weeks after the biopic inspired by the biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer was released, its box office sales brought in over half a billion dollars. Oppenheimer tells the story of "the father of the atomic bomb and the Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear weapons and went on to detonate the first nuclear weapon near the Latino village of Tularosa and the Mescalero Apache Reservation on July 16, 1945."

More from MamásLatinas: Perfect places in the U.S. for families who love the outdoors

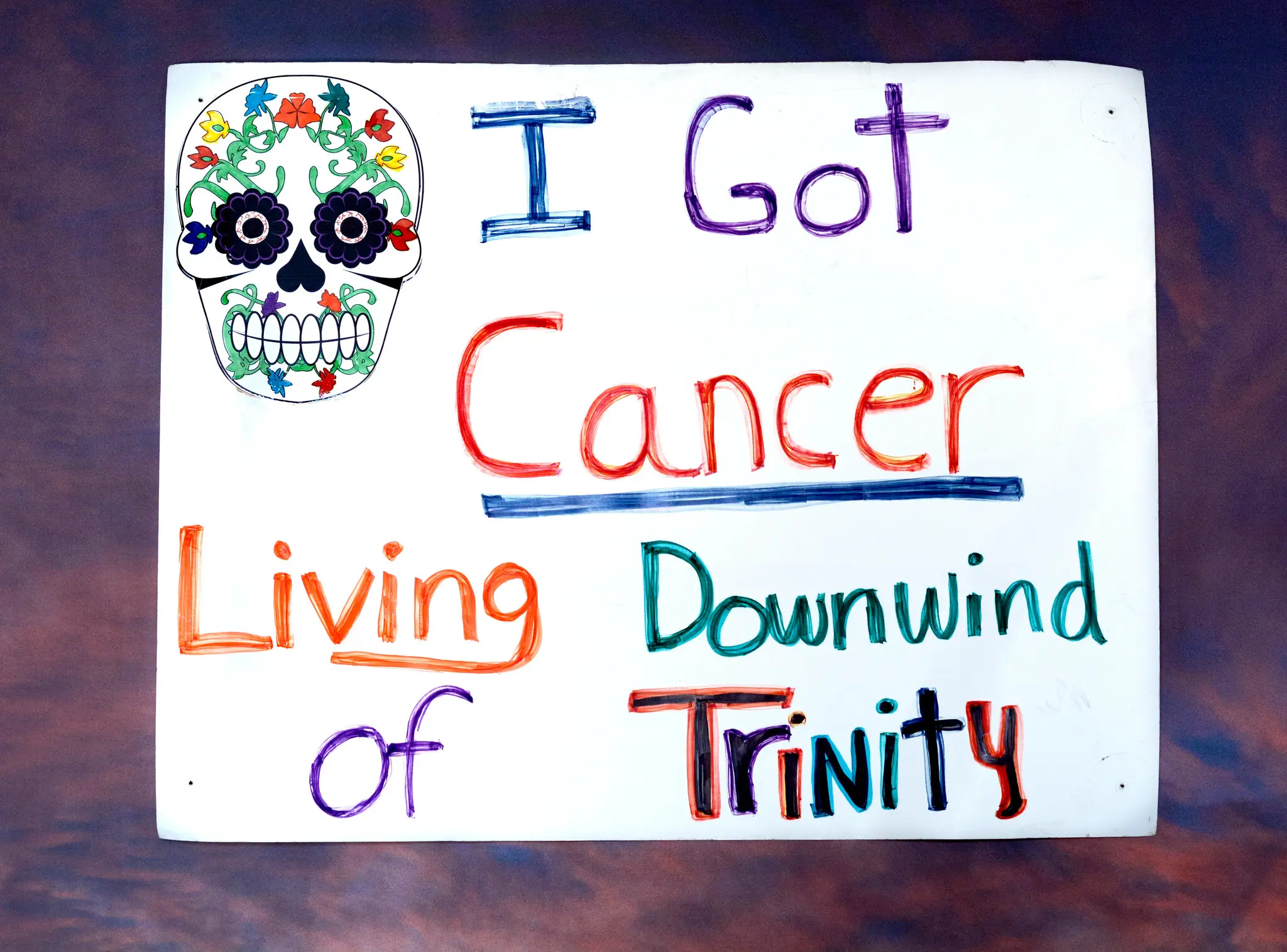

Any film that is based on historical events, has the potential to educate and acknowledge previously unacknowledged wrongs. But that's not what the film has done for some residents of southern New Mexico, who are still dealing with the literal fallout of the radiation from the detonation of that bomb generations ago. As Tina Cordova, cofounder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, writes in an opinion piece for the New York Times: "One film can't do it all, but I can't help feeling that the retelling of this story, as it stands, is a missed opportunity." Thankfully, there are people like Cordova, who refuse to be "left out of the narrative." Let's dive into that narrative and how it "has had devastating health consequences."

The area where the bomb was tested was not deserted.

The Trinity test, as it was called, happened in an area where there were more than 13,000 New Mexicans living within a 50-mile radius and get this: Many of the people who lived in that radius were never even told that a bomb was being detonated. Imagine the fear and having an explosion of that magnitude happen hear you would cause when you have no idea why it is happening.

Contaminated ash rained for days.

Radioactive ash fell from the sky for days after the detonation. According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the radiation levels near homes in the area reached “almost 10,000 times what is currently allowed in public areas.”

The radiation people were exposed to has caused horrifying health issues.

Cordova writes:

“That fallout has had devastating health consequences. While I know of no people who lost their lives during the test, the organization I co-founded has documented many instances of families in New Mexico with four and five generations of cancers since the bomb was detonated. My family is typical: I am the fourth generation in my family to have had cancer since 1945. My 23-year-old niece has just been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. She is a college student studying art. Now her life, too, has been upended.”

To this day, the government has offered no compensation to those affected.

In 1990, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was passed. It is a federal statute “provides payments to individuals who contracted certain cancers and other diseases as a result of exposures to radiation released during aboveground nuclear weapons tests and/or during employment in uranium mines.” The statute expires in 2024 and for some unfathomable reason, New Mexicans exposed to radiation because of the Trinity test are not eligible for compensation.

Would the US government have turned a blind eye to the devastation if the residents of southern New Mexico were non-Hispanic whites?

It’s hard to believe that if the residents of southern New Mexico, who were affected by the radioactive fallout of the bomb, were not predominantly Hispanic or Indigenous that they would have been left to deal with the consequences for generations to come. We cannot change the past, but we cannot as a people afford to ignore it or continue to let others try to erase it.